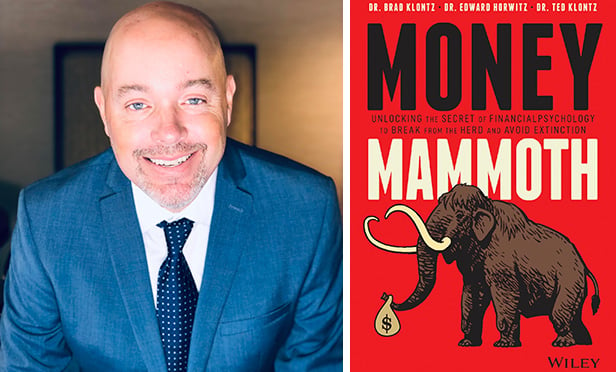

Brad Klontz

Brad Klontz

It's never too soon for financial advisors to help folks develop a healthy mindset about money. That's why, sporting a baseball cap and stylish beard, financial planner Brad Klontz, also a clinical psychologist, teaches personal finance to Gen Z on TikTok.

The behavioral finance expert, who does this via lightning-fast entertaining videos, has 205,000 followers, and his most popular video has drawn more than 4 million views.

Perhaps the most gratifying aspect for Klontz, managing principal of Your Mental Wealth Advisors, is showing teenage day traders studies indicating how their habit is a losing proposition, a tack that often prompts them to quit doing it, as Klontz tells ThinkAdvisor in an interview.

Meanwhile, in his practice, the planner manages $350 million in client assets and coaches ultra-high net worth family businesses, and others, on wealth-related issues.

In the interview, Klontz, who has partnered on projects with firms including Capital One and JPMorgan Chase, discusses how he assuaged clients' anxiety amid the big pandemic-provoked March market collapse.

His newest book, "Money Mammoth: Unlocking the Secrets of Financial Psychology to Break from the Herd and Avoid Extinction" (Wiley), is slated for Nov. 3 publication.

In our conversation, Klontz argues that financial advisors who dismiss behavioral finance and financial psychology as inconsequential are "potentially facing extinction."

An associate professor of practice in financial psychology and behavioral finance at Creighton University, Klontz is a fellow of the American Psychological Association and co-founder of the Financial Psychology Institute, which trains financial and mental health professionals.

Klontz is indeed no stranger to helping young people. For 20 years, living in Kauai, Hawaii, he worked with high school students to change their mindset on a variety of teenage issues.

And that circles back to TikTok, where Klontz applies the psychology of wealth and personal finance in lively 15- to 20-second videos that enlighten Gen Z about things such as to have "a rich mindset." His top hit reveals an approach to score an "A" on "every test you'll ever take again."

@dr.bradklontz This study tip is how I became a doctor ##WelcomeWeek ##ShowAndTell ##StudyTips ##TikTokPartner ##LearnOnTikTok

ThinkAdvisor recently interviewed Klontz, speaking by phone from his base in Boulder, Colorado. He was just back from recording a continuing education video for Michael Kitces' firm. The psychologist describes it as "proven techniques to help clients who are resisting your advice."

In the interview, he discusses his research on how to motivate clients to save more for retirement by "inspiring their animal brain."

Here are highlights of our conversation:

THINKADVISOR: Seems pretty offbeat, but you teach Generation Z about finance on TikTok. You began last October. Do you get many comments?

BRAD KLONTZ: Hundreds a day. My favorites are "I started saving because of you." Or "I stopped day trading because of you."

Are there really that many teenage day traders?

Oh my gosh, yes. I got on TikTok because there were all these videos on it showing how to be a day trader. But I don't tell people not to day trade. I just show them studies that [indicate] the success rate of day trading: It's horrendous. Every time someone comments: "I lost a bunch of money day trading, but I decided to stop after I watched your videos, I'm like, "Great!"

Do you have very many followers?

This is the crazy part: I have more teenagers following me on TikTok than financial planners following me on LinkedIn.

Wow. Let's talk about advising your clients. Amid the pandemic, in general have people's relationship with money changed?

There have been some short-term changes for sure. Many people have dramatically reduced spending because their income has taken a hit. And, even if they didn't lose their job, they're very concerned about an emergency fund. So a lot of people have become more conservative. The proof, though, is in the lasting impact.

On whom?

There's going to be an impact on an entire generation: the most impressionable generation, young adults — the millennials.

How else have clients' relationship with money changed?

For many people, there's a foreshortened sense of future in terms of what really matters: They're thinking that the life they have could go away. I've noticed a lot of existential questions. [They're pondering] the meaning of life. The pandemic is a wake-up call to look at your life. Are you living the life you want?

How does that thinking manifest in practical ways?

People are asking, "Do I really want to live where I'm living?" So it's not about wanting to just take money out and spend it on things, which is actually harder because of the pandemic.

Why are people so focused on relocating?

Worries about [catching] the coronavirus are part of it. I've noticed that a lot who live in concentrated, high-density population areas are reflecting, "Maybe I should move out to the country or someplace where there are fewer people." Perhaps a little town in the middle of nowhere has never seemed quite so desirable.